The ‘Invisible Mold’: How Do Catheters Get Their Shape Without Getting Stuck?

Hold a sophisticated medical catheter in your hand, and you are looking at a deceptive object. It looks like a simple piece of plastic tubing. In reality, it is a high-tech composite sandwich.

A modern cardiac or neurovascular catheter is composed of multiple layers: an ultra-slick inner liner to let tools slide through, a stainless steel or nitinol braid for structural strength, and a soft outer jacket to prevent injury to the blood vessels. These layers are fused together into a single, seamless unit that must be flexible, torqueable, and precise to within a fraction of a millimeter.

But here is the engineering puzzle: How do you melt three different layers of plastic together into a perfect tube without the tube collapsing on itself? And once it cools, how do you make sure the inside is perfectly hollow?

You cannot use a standard mold, because the object is long and thin. Instead, you have to build the device inside-out, using a temporary skeleton.

The Lamination Process

The manufacturing of these devices relies on a process called “Reflow Lamination.”

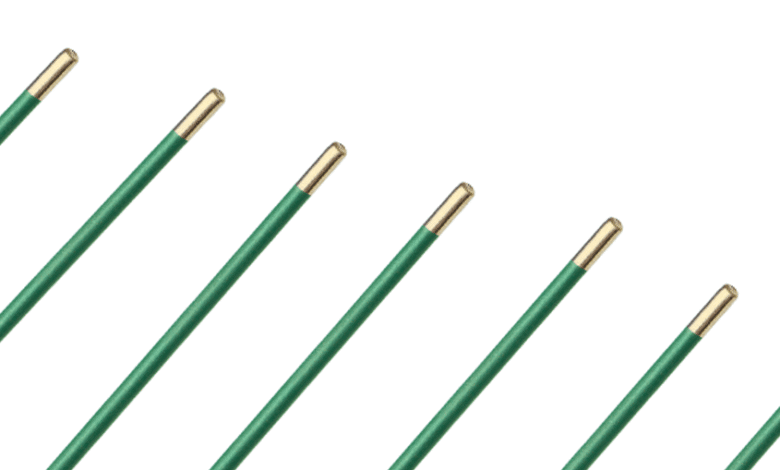

It starts with a solid metal wire. This wire is the “master” for the inside of the catheter. If the wire is 0.010 inches thick, the inside of the final tube will be exactly 0.010 inches wide.

Engineers slide the inner polymer liner over this wire. Then, they weave the metal braid over the liner. Finally, they slide the outer plastic jacket over the braid. It is like putting on three layers of socks.

Once the layers are assembled, the whole thing is subjected to heat—usually via a heat shrink tube or a thermal nozzle. The heat melts the plastics. They flow through the gaps in the metal braid and bond to each other. They “reflow” into a solid, unified composite.

The “Release” Problem

This is where the physics gets tricky.

When polymers melt, they become sticky. They want to adhere to everything they touch. In the reflow process, the plastic effectively glues itself to the central metal wire.

But the wire cannot stay there. It has to be removed to create the hollow lumen of the catheter.

This creates a massive friction problem. If you try to pull a three-foot-long metal wire out of a tight, sticky plastic tube, the friction can be immense.

If the friction is too high, one of three disasters happens:

- Elongation: You pull the wire, and the plastic tube stretches out like a rubber band. This changes the dimensions and ruins the precision tolerances.

- Delamination: The force of the pull rips the inner liner away from the outer jacket, destroying the structural integrity of the device.

- Buckling: The tube collapses or kinks like a bent straw.

The Coefficient of Friction (CoF)

To solve this, engineers must lower the “Coefficient of Friction” between the core and the plastic. They need the wire to be slippery—supernaturally slippery.

Standard stainless steel, even when polished, is not enough. Under a microscope, steel has peaks and valleys. Melted plastic flows into these valleys, creating a mechanical lock. When you try to pull the wire out, you are essentially trying to shear off thousands of microscopic plastic anchors.

The solution is to coat the wire in a material that has one of the lowest surface energies of any solid known to science: Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE).

The Chemistry of Non-Stick

PTFE is a fluoropolymer. Its carbon-fluorine bonds are incredibly strong and non-polar. This means they have almost zero interest in bonding with other atoms (Van der Waals forces). It is chemically aloof.

By coating the manufacturing wire with a precise, microns-thin layer of this material, engineers create a barrier. When the catheter plastics melt during the reflow process, they flow over the wire, but they cannot grab the wire. The coating fills in the microscopic valleys of the steel, creating a perfectly smooth, chemically inert surface.

The “Slide” Factor

Once the assembly cools, the engineer pulls the wire. Because of the coating, the bond is non-existent. The wire slides out effortlessly. The catheter remains perfectly shaped, unstretched, and structurally sound.

This “release capability” is the defining metric of a manufacturing process. It allows for the creation of incredibly long, tortuous shapes that would otherwise be impossible to demold.

Conclusion

The miracle of modern minimally invasive surgery—the ability to snake a device through the brain or the heart—depends entirely on the precision of the tubing. That precision is born in the heat of the reflow process.

It is a delicate dance of thermodynamics and tribology. Manufacturers must melt materials to bond them, yet prevent them from sticking to the very tool that shapes them. By utilizing high-precision ptfe coated mandrels as the foundational core of the build, engineers ensure that when the heat is applied, the only thing that sticks is the design intent, not the device itself.